How I Write

A behind-the-scenes look at how notebooks, memory, research, and rhythm shape the words I put into the world.

Hello everyone,

A quick note before today’s post—

I’ve been off my regular weekly rhythm the past two weeks, and I wanted to thank you for your patience. I haven’t missed a week since early January, but I’ve been deep in hermit mode finishing a publishing project that demanded my full attention. The good news: I’m back, and the weekly rhythm resumes starting now.

Paid subscribers—you’ll receive an extra bonus post soon as a thank-you, and Field Notes from the Imagination will return this Friday.

Also, I’m extending the 50% off offer on all my courses through the next new moon—May 26th. So if you upgrade to a paid subscription, you’ll receive half off all of my digital formation resources (available to both new and longtime paid subscribers).

Thanks again for your grace and support. Now, on to today’s post.

PS: Many of you have inquired about creative coaching. I have not forgotten you. The publishing deadline delayed my response. Please forgive the delay. Expect a response shortly. Thank you for your patience. 🙏

Prologue: This Is Not a System

This isn’t a prescriptive guide or a list of productivity hacks. I’m not here to sell a method (although I am developing a “formation journal” that you guys will love). What follows is a behind-the-scenes look at how writing actually happens in my world, at least most of the time.

Writing is not one thing. It’s not even the same thing every time. Some days it’s a free-flowing rush; others, it’s slow, hard labor. Sometimes it starts with a quote I scribbled in a journal weeks ago. Sometimes it starts with a question I can’t stop asking. Most often, it starts with a cup of tea.

What you’ll find here is a glimpse into how I write—how I think, prepare, shape, struggle, and eventually, let the words go.

The Threshold: The Idea vs. The Act

I’ve lost count of how many people have told me they love writing—or that they’re “thinking about” writing a book. I don’t doubt their sincerity. And I believe everyone has a story to share—everyone should spend the time to write it down if they can.

But I also believe there’s a difference between loving the idea of writing and doing the actual work of writing.

That distinction shows up everywhere in life. People love the idea of travel, of marriage, of parenting, of ministry, of starting their own thing. But loving the idea isn’t the same as living the reality. Writing is no different.

I’ve had people look at my life and say, “Must be nice—to be a writer, to have a PhD, to have the time to think and create.” But what they don’t see is the daily labor underneath it all. The hours. The wrestle. The relentless return. The path isn’t paved with aesthetics—it’s carved by endurance.

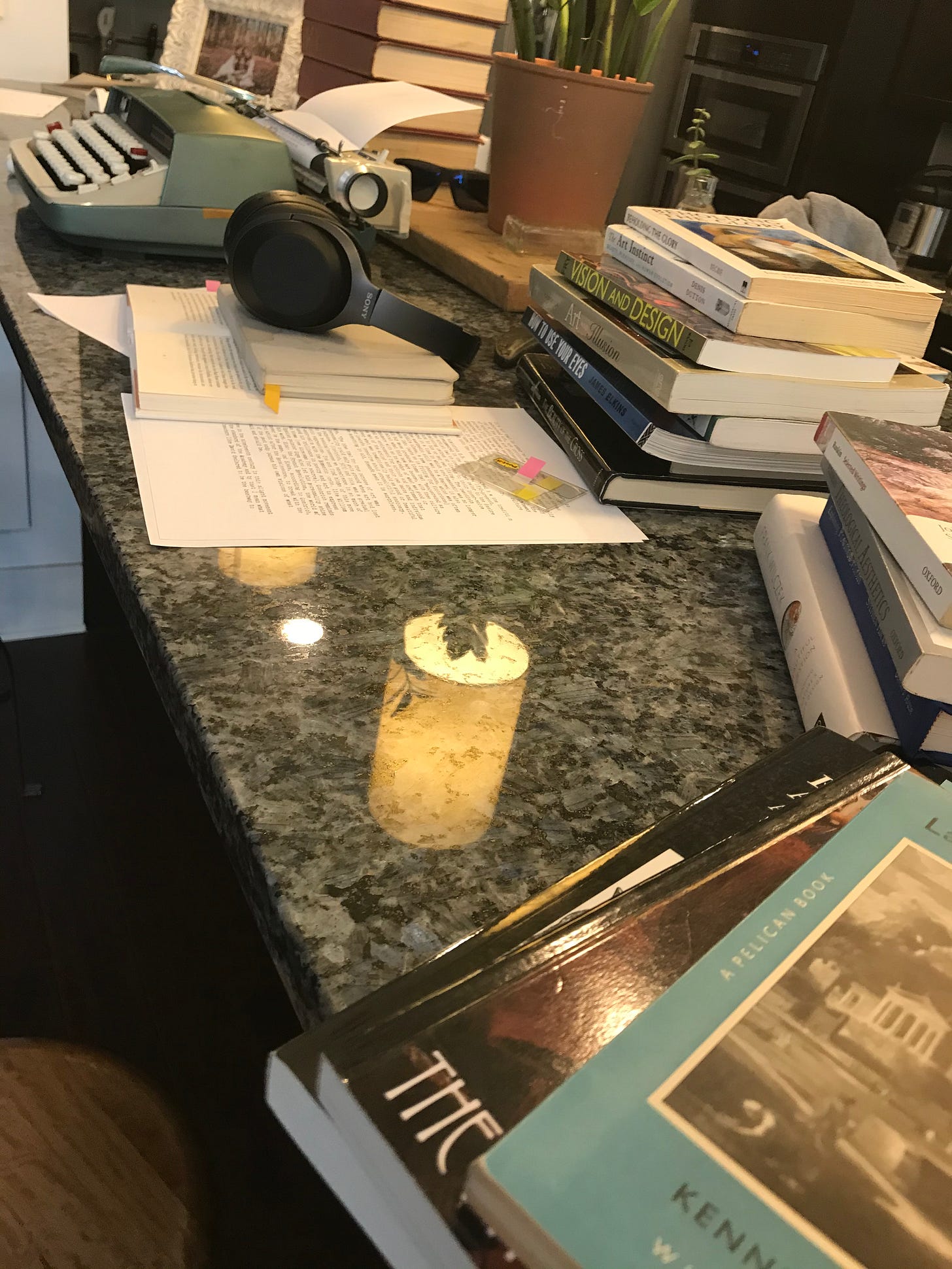

The romantic picture still lingers for many: the attic desk, the scattered pages, the candlelight, the quiet fury of inspiration at 2:00 a.m. And yes—I’ve lived versions of that. I’ve written by candlelight. I’ve laid pages across the floor. But writing that lasts—writing that reaches others and reshapes ideas—requires more than ambience.

We live in the age of aesthetic. Of vibe. Where “the feeling” wins. We also live in the age of the final product—people want the book without the drafts, the highlight reel without the practice.

People marveled at Michael Jordan’s final product on game day. But few were willing to embrace his regimen, his mentality, his years of silent grind.

The idea of Air Jordan inspired many. But who was willing to walk the path that led there?

It’s the same with writing.

William Zinsser once told the story of being asked to speak at a conference on writing. Another speaker on the panel painted a romantic picture of the writing life—fluid, aesthetic, liberating. Zinsser marveled at the man’s response and countered bluntly:

“It’s hard work. A clear sentence is no accident. Very few sentences come out right the first time, or even the third time. Remember this in moments of despair. If you find that writing is hard, it’s because it is hard.”

I think both are true. The act of writing is beautiful.

But as Roger Scruton said of all beauty: Beauty is difficult. It demands attention, discipline, and sacrifice.

For writing—or any creative pursuit—to become anything real, it has to become work.

The Rigor: Why It’s Still Worth It

I started writing as a young man, and like most of us, I started from joy. From sheer creative overflow. I wrote songs, poems, and short stories. I didn’t worry about structure or clarity. I didn’t even worry if it made sense. It was expression for its own sake.

Early in my career (as a twentysomething), I wrote from passion and reaction. I loved words. I loved to rant. I definitely had opinions. But structure? Logical flow? Those felt like constraints to the creative spark.

Pursuing structure doesn’t kill creativity—it delivers it.

It wasn’t until later—first in grad school, then in my PhD work—that I began to understand how form could be freeing. I learned that the structure of books and ideas didn’t restrain passion; it refined it. It gave language a frame. And that frame made the message beautiful.

A lot of younger writers—or anyone who identifies as “creative”—tend to think that structure hinders imagination (like I did!). But the opposite is true. This is true not just in writing, but in carpentry, painting, music, teaching, and even speaking fluidly in a way that others can follow.

Pursuing structure doesn’t kill creativity—it delivers it.

Whether you’re writing a novel or a dissertation, a poem or a platform post, the work has to hold. A novel still needs narrative momentum. A nonfiction book still needs an arc. A PhD thesis is governed by logical flow, persuasive architecture, and the disciplined unfolding of research. The rigor creates the runway for your voice to lift.

It’s the same in visual art. The painter is not stifled by the canvas. The canvas makes the painting possible. Color theory, tone, value, and composition aren’t restrictions. They’re what turn chaos into beauty.

C.S. Lewis writes about this in The Weight of Glory, describing the young man who longs to read Greek poetry. But in order to do that, he first has to learn Greek. Which is hard. It’s not glamorous. It doesn’t feel poetic. But if he endures the rigor, he’ll one day read the glories of Homer, of Sophocles. And that discipline won’t diminish his love of poetry in English—it will amplify it.

The reward, said Lewis, is not tacked on to the end of the discipline. It is the crown of the discipline itself.

That’s how it works with writing.

The rigor creates the runway for your voice to lift.

The rigor is not punishment. It’s the path.

And the joy? The joy always returns—usually when I’ve stopped looking for it.

The Depth: Why Writing Requires Living

“Write what you know” is a phrase that gets tossed around, and it’s both overused and underestimated. People tend to interpret it literally: write about your hometown, your childhood, your job. But that’s not the phrase’s full scope of meaning. It’s not just static observation, it’s about dynamic participation.

Writing what you know is about living awake. It’s about going deeper into the world you already inhabit.

I once told a young woman stories from my twenties—early adventures, close calls, serious risks, big questions—and she stopped me mid-sentence and asked how old I was. “There’s no way you’ve lived all of that,” she said.

Now, that made me laugh. And, it was satisfying to hear.

Because I had lived it all. Not because I’ve seen the whole world, but because I’ve lived with attention. With presence. I’ve tried things and failed. I’d risked things and won. And through it all, I paid attention. And that’s the writer’s job.

If you want to write, you have to read. But you also have to live. And remember. And pay attention.

The Tools I Use

Like my “How I Study” process, this is where things get practical. These are the tools and rhythms I return to again and again.

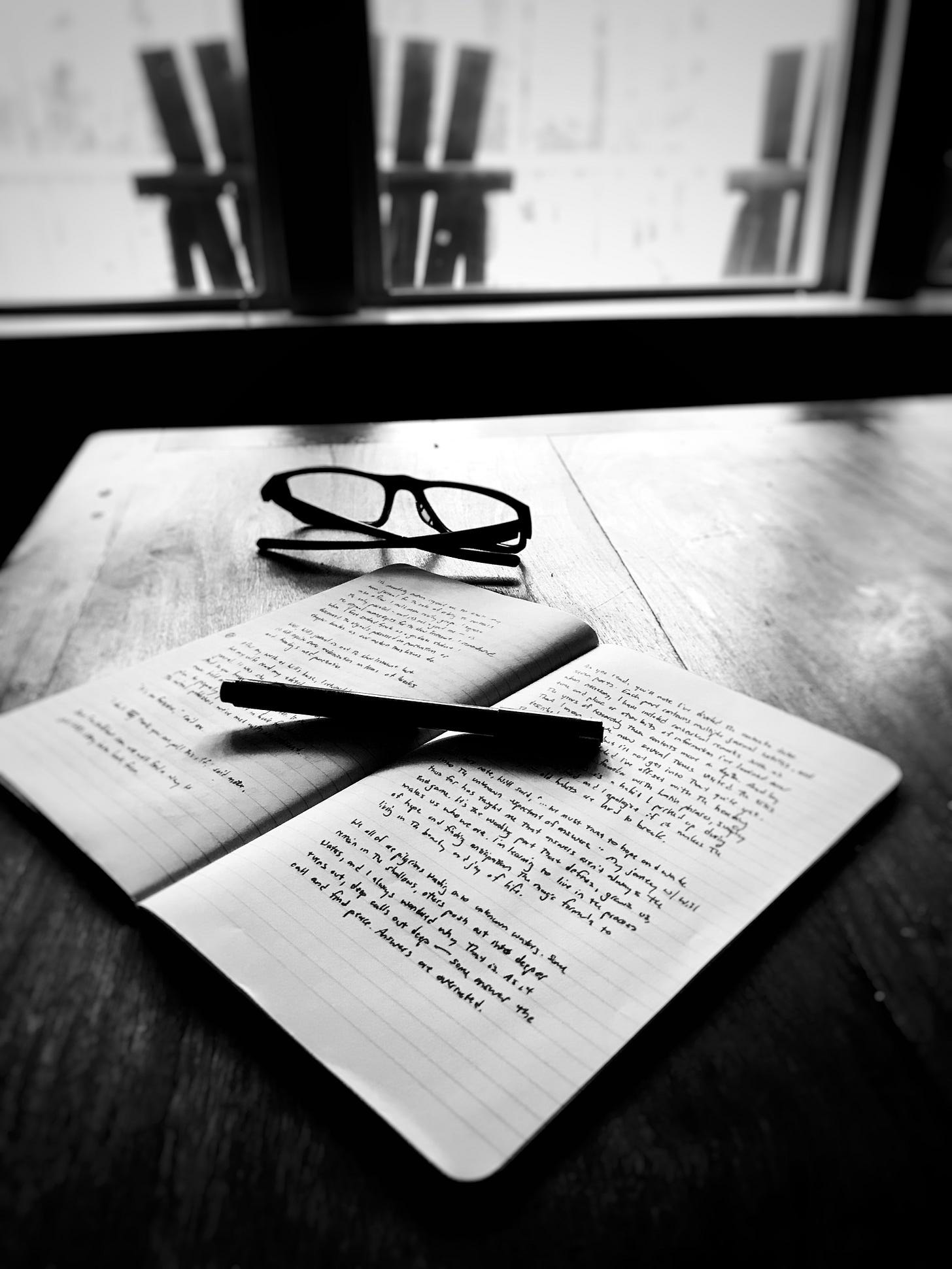

1. I begin with longhand.

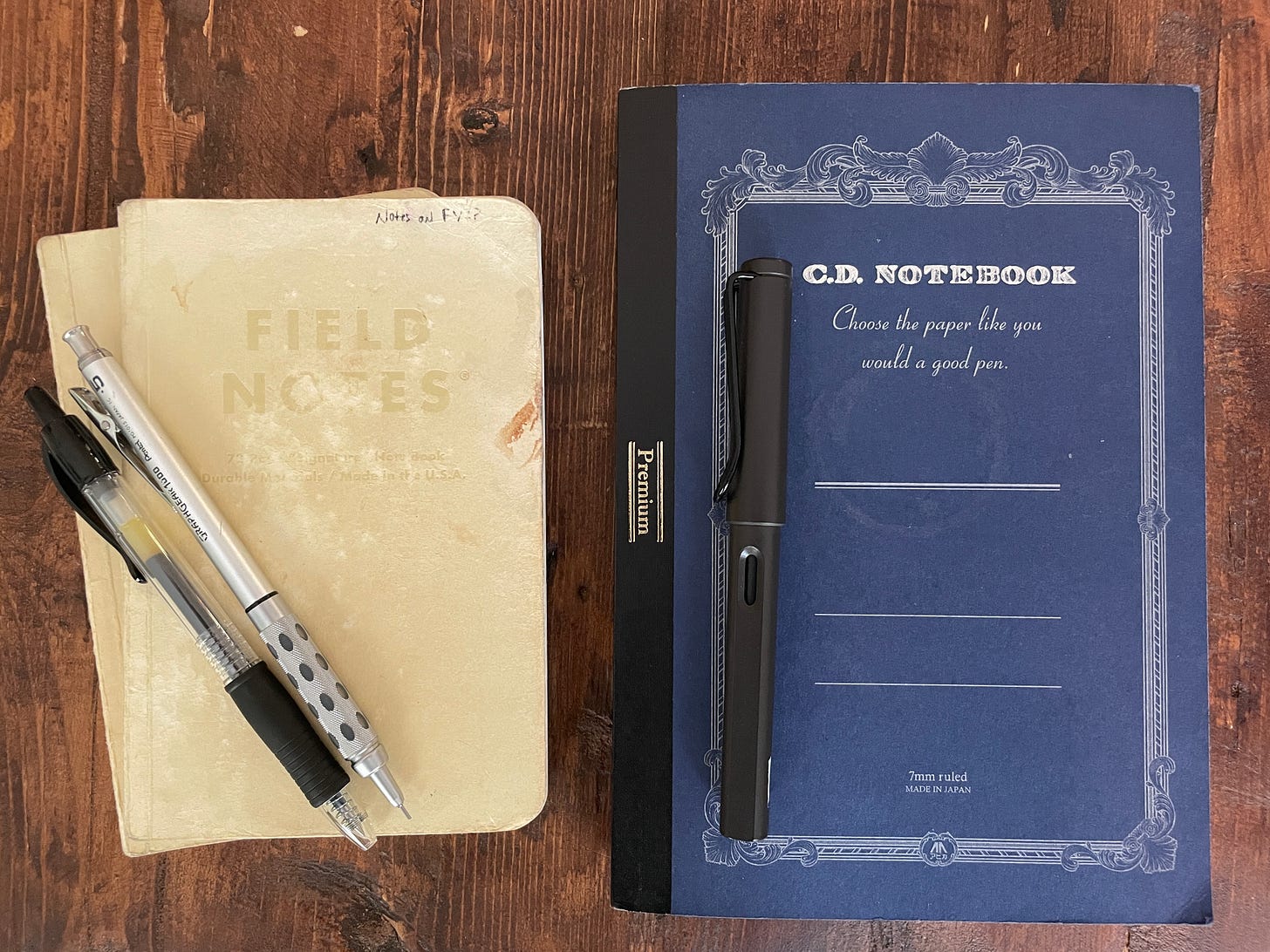

Every writing session begins with a pen—not a keyboard. I use a Lamy fountain pen or a Pilot G2 .07, writing in softback Japanese notebooks that are always nearby. Longhand slows my thinking to the speed of reflection. It makes me choose my words. It connects my mind to the page in a way that screens never can.

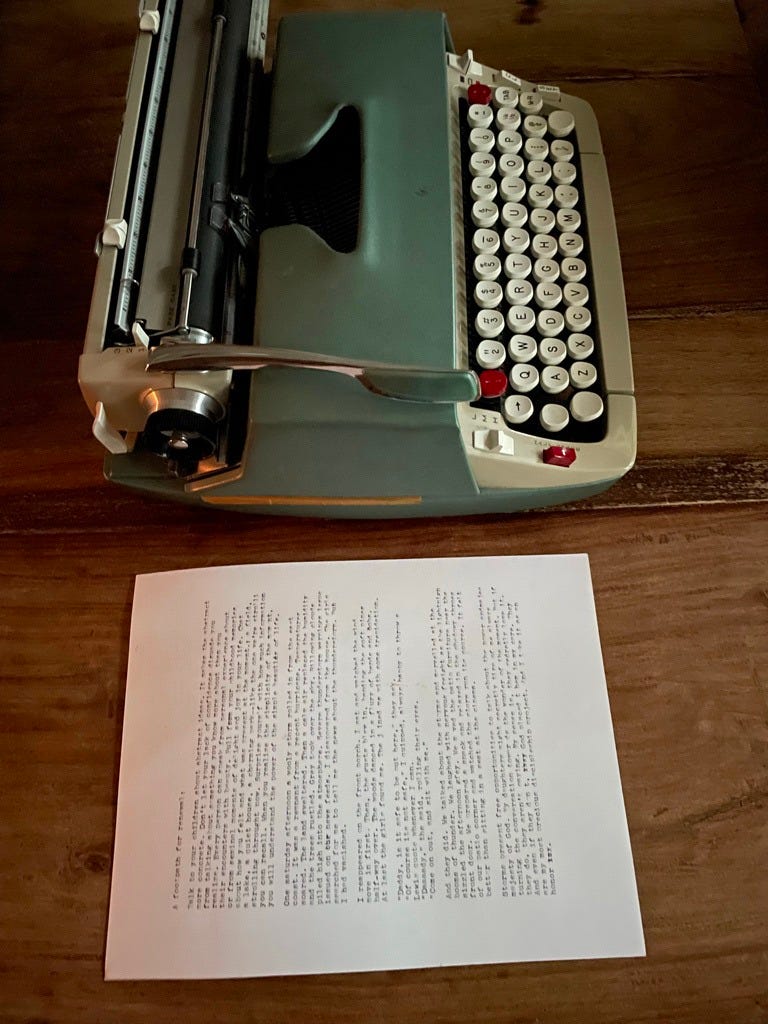

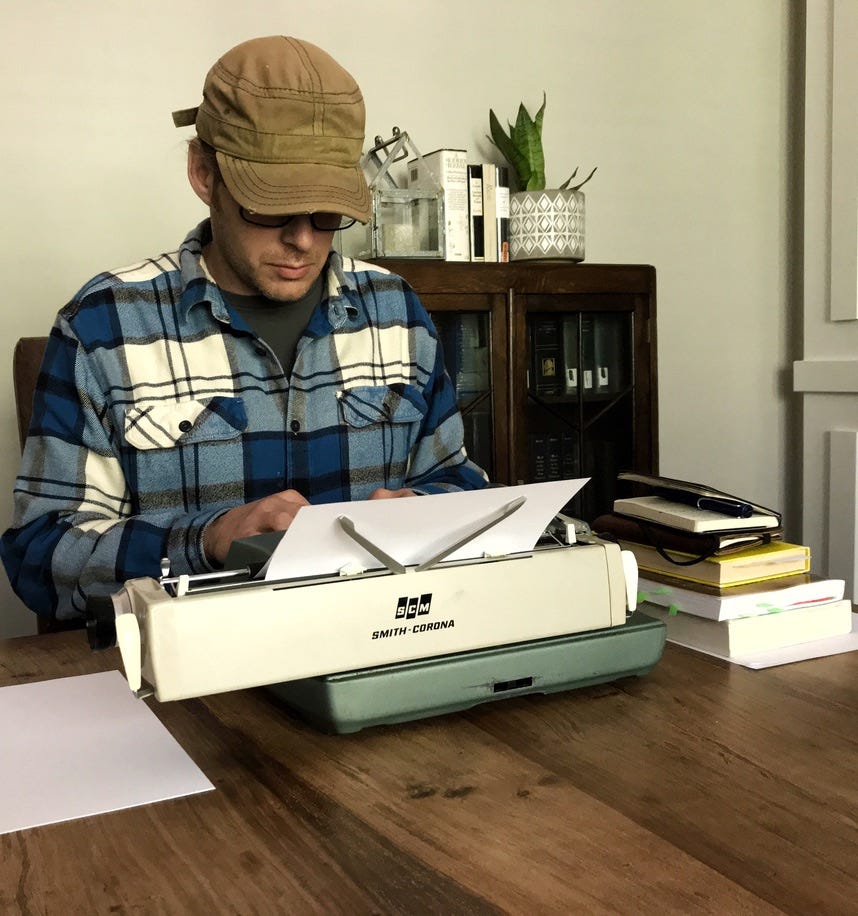

MIT researched Nietzsche’s prose before and after he used a typewriter. The result? His prose declined when he switched to a typewriter. C.S. Lewis refused to use one altogether. I do use one—for rhythm and novelty, I mean, they’re just so fun!—but my deepest writing always begins with pen and page.

2. I write in silence—with a soundtrack.

It sounds contradictory, but it’s not. I usually begin my sessions with a cup of tea (English Breakfast or Earl Grey with whole milk and honey). I put on music: ambient, classical, or reflective piano. Music is always playing in our home—it's the hum beneath our life—and it follows me into my writing. I use multiple playlists on YouTube music. And, no, I don’t use Spotify. 😎

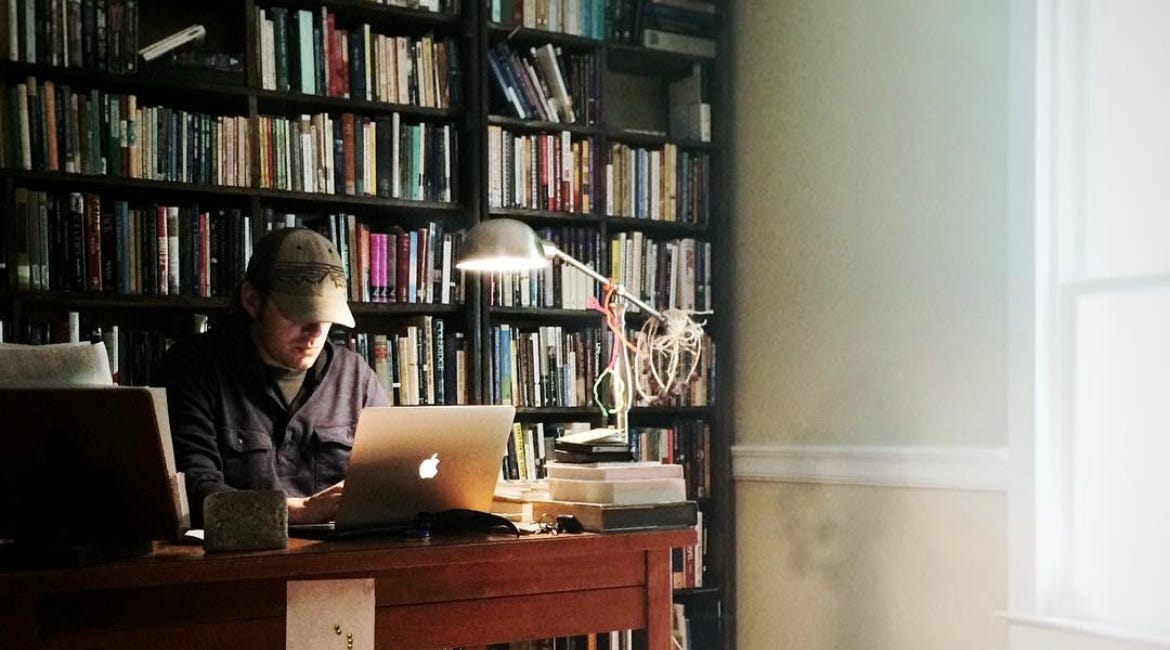

3. I structure in Scrivener, refine in Word.

Scrivener is where I map and organize. Word is where I revise. Years ago, I was opposed to Scrivener, but my friend Ann spoke so highly of it, I gave it a try and haven’t looked back. It’s like a DeWalt circular saw—it just works, and is irreplaceable. I’ll have to do a workshop on how I use it. Oh, wait, I already did! It’s in one of my Writer’s Workshops. The bundle is on sale right now. (See what I did there? 🤓)

If you become a paid subscriber on my Substack, you’ll receive 50% off the Writer’s Workshop bundle. Or you can click here to purchase.

My projects are divided by genre and audience: academic monographs, novels, Substack essays, non-fiction book ideas, poetry collections, and client work. Each has a folder, a flow, a pulse. I’m working on a future post that goes into nerdy detail on how I structure my folders on my MacBook Pro. Stay tuned.

4. I archive with Zotero.

Zotero helps me store, cite, and retrieve hundreds of books and articles. If you do any serious research writing—especially in theology, philosophy, or the humanities—it’s indispensable.

5. I protect my creative momentum.

I don’t force it, but I do show up for it. The key is giving myself space to wander in the beginning, then narrowing as the piece takes shape. That’s how momentum builds—through reflection, exploration, and disciplined return.

The Session Itself: How I Actually Write

The actual writing session often begins before I sit down. It starts outside—on the terrace, journal in hand, reading something dense and evocative: aesthetics, philosophy, poetry, Lewis, Kant, Wordsworth, Scruton.

I read across genres and eras. I follow questions. Then I begin writing—not to publish, not to post, but to think. These journal pages are wandering, questioning, raw. Sometimes I write out of joy. Sometimes out of tension. I let myself push the edges of belief, explore nuance, name uncertainty.

This is not the public-facing work. But it’s what gives rise to it.

From there, I move to the computer. I rewrite what I journaled. I don’t just transcribe—I translate the thought into clarity. Then I move into research—either light (Google, ChatGPT), or deep (pulling primary texts, diving into annotated volumes).

This is the work of synthesis. Not just quoting someone, but absorbing their thought and pushing it further.

Augustine may have spoken of the weight of glory, but it was Lewis who gave it form. That’s the writer’s task: to reframe truth for your generation without diluting its weight.

So I return to the books, to the thoughts I’ve scribbled, to the lingering questions. I write, rewrite, source, prune. I cut paragraphs. I shape the voice. And if I’ve done the work right, what started as a splinter of thought becomes something whole—something that speaks.

Why I Still Write

Even on the hardest days, I come back to the page.

Writing is how I pay attention. It’s how I remember. It’s how I work through ache, wonder, doubt, and devotion. It’s not always beautiful. But it’s always mine. It’s one of the ways I offer myself to the world, and back to God—writing is worship.

Sidebar: Questions I Often Get About Writing

A few honest answers from the trail. These represent a synthesis of some of the questions I often get from friends, family, and readers like you.

Do you set daily word count goals?

No. I don’t write by quota; I write by momentum. I know some people need to set daily word count goals, and that is great, but I don’t work that way. Over time, you will build the “writing muscle,” as I like to call it, and eventually, using a word count quota to motivate you will become obsolete.

Some days, I write thousands of words. When I wrote my book Veneer, I wrote an entire 6,000-word chapter in one day. Was it all good? No. Was it all included in the book? After revisions, it was just over 5,000 words. I care more about rhythm than volume. And when in rhythm, the rules of the world no longer apply.

I think it comes down to how you’re wired and also your source material. If you are reading deeply and broadly, studying deeply and broadly, and staying disciplined in synthesizing your thoughts onto the page, you will never lack for word count. I believe that when you write from that place of wonder and epiphany—what you’re learning—you will be able to write enough words to fill the sky.

Discipline gets you to the desk. Delight keeps you there.

How do you finish big projects?

As I mentioned above, I’ve built the muscle of writing over the years. In grad school, a Cambridge-trained professor once told me:

“In academia, wit doesn’t matter. Discipline does.”

{Stanley Hauerwas said this, too.}

Half the students in his doctoral program at Cambridge didn’t finish—not for lack of “brilliance,” but because they hadn’t trained the habit of writing.

Writing is an endurance sport. You don’t train for a marathon by sprinting once a week.

Do you write every day?

Yes. But not everything is public-facing. And it’s what I write in the quiet shadows of my morning terrace times that fuel what finds its way into books, talks, stories, and posts like this one.

What do you do when you get stuck?

I don’t get stuck.

Meaning, I’ve never experienced what people typically call “writer’s block.” I’ve thought a lot about this over the years, and I think the reason is simple: it’s not how I approach writing.

I don’t sit down at my desk for a neatly contained “writing session,” block off an hour, and expect magic to happen. I write from morning until night—sometimes on paper, sometimes in my head. I don’t divide my life from my writing life. It’s all the same life.

Here’s what I’ve noticed: most people experience writer’s block when they’re trying to write one thing—and only that thing. A project, a post, a paper, a novel. But their inner fear kicks in. Fear that the idea isn’t good enough. That they aren’t good enough. The scope gets too narrow. The pressure builds. And the words stop coming.

But when you live as a writer—when writing is always happening, even in fragments—that pressure doesn’t accumulate. Because you’re not waiting on brilliance to strike in one perfect sitting. You’re gathering, capturing, listening, learning.

I’ve learned to take the risk, write the idea, and not fear it. I put it down and let it sit there. It doesn’t have to be perfect. It just has to exist.

The best way I can explain this is to tell you about a time I experienced the complete opposite of writer’s block.

When I was writing The Tempest and The Bloom, one of my novels, the words poured out of me. I laughed. I cried. I felt delight. The first draft took me a couple of weeks. That novel is centered around a character named Aylin, who is beauty incarnate. And I had just finished a PhD on beauty and northern aesthetics. My well was deep. I wasn’t scraping for ideas. I had something to say—about beauty, about myself, about the world.

The preparatory work of study fueled the imaginative work of story.

So if you’re someone who struggles with “writer’s block,” here’s my advice:

Don’t start by writing. Start by reading. Start by thinking.

Wrestle with ideas. Discuss them with a friend. Study. Annotate. Let them get under your skin. Mark pages where a line grabs you. Write in the margins. Highlight with a red watercolor pencil. Record a voice memo in your Notes app, like a doctor dictating a patient reflection. Speak into ChatGPT. Begin an audio archive: LOG: #001 – Beauty and the Darkness. Take a walk. Bring your journal. When a thought arises, grab it. Write it down. Keep walking.

All of this is writing.

None of it is blockage.

If you want to delve deeper into my thoughts on how studying fuels writing, check out this post:

How I Study: My Five-Step System for Deep Study and Lifelong Learning

The Beautiful Disruption thrives on the generosity of readers like you. If you enjoy these posts and wish to see them grow, become a free or paid subscriber—your support truly makes a difference.

How do you know when a piece is done?

When I read it out loud, it makes sense to my mind, delights my ears, and makes me smile. Like painting with oils, sometimes you have to know when to stop fiddling—because you’ll fiddle it to death. There is such a thing as overwriting and overediting. Let it sit. Let it breathe. When it’s clear, let it go. Hit publish. Hit send. It’s not the end of the world. There are more ideas, more words, and more time to sit with your thoughts.

I’ve revised The Tempest and The Bloom five times. Is it done? Sure. Is it done? Nah. Is it done? Maybe.

Fin

I hope this post inspired you. I hope it cracked open your imagination and got you fired up to write. But more than that. I hope it fired you up to live. Because that’s where writing begins.

Leave a comment below. It can be a question, a reflection, a note on how you relate to this post or your own process in writing or creating. Let’s learn together!

Dear Timothy, thank you so very much for your post. It actually might be an answer to one of my prayers. I was praying recently to God about my writing, asking Him to show me if it was worth investing in it. You see, I am French and a convert since 2010. Being a Christian in France is not an easy thing . France is probably one of the most secular, atheist and anti-Christian European countries. I have writing a bit in English, but my prayers were really about wether or not I should be bold enough to try and write about my faith in French, and maybe to start writing on Substack in French. One day Ann Voskamp encouraged me to be a « bold light » in my country. I love your writing and it is always inspiring to me. Thank you for this article that inspires me to take her advice and make it a reality ! And , like others here , I do hope to read a new book from you soon. Hugs from France

There’s something about your writing in this season that is just igniting flames in my soul! It’s one of the voices -along with morning light and poetry and mindful cooking, etc- in this song I’m hearing… this summons. To what in particular? I don’t have a clue. But in its deepest sense it’s a call to live. Live!

I’m not a writer, but I am beginning to write as a way of thinking and experiencing, like you said. (Most) every day in May, I’ve been sitting outside and experiencing the sunrise and then writing about it. It has been astonishing to see how much knowing I’m going to write about it opens my senses to experience it far more deeply.

PS I was hoping that your silence on here meant that you were doing extra writing. I can’t wait to read the results! (Here’s hoping it’s more work on the human density idea. 🤞🏼🤩)