What Van Gogh and C.S. Lewis Teach Us About Calling

Thoughts on finding joy in pursuing what you love.

Vincent Van Gogh wasn’t trying to make an art statement about himself. He was trying to make paintings that brought joy and consolation. By creating works that evoked joy, he produced peace in his troubled mind and delighted others.

In a letter to his brother, Theo, Vincent describes the aim of his now-famous sketch, “The artist’s room in Arles” (1889).

“… to look at the picture ought to rest the brain or rather the imagination. The walls are pale violet. The ground is of red tiles. The wood of the bed and chairs is the yellow of fresh butter, the sheets and pillows very light greenish lemon. The overlet scarlet. The window green. the toilet-table orange, the basin blue. The doors lilac.”1

Through color and composition, Vincent communicated his feelings about what he saw, aiming to ease the viewer's imagination. How different from the naked self-expression of today. Contemporary art—broadly understood—is about ultimate self-freedom, unbridled expression, and even transgression. When do we ever hear anything about serving the audience?

Painting was Vincent’s vocation. Art historian E.H. Gombrich said Vincent and Cézanne had all but given up on the idea that anybody would pay attention to their pictures. “They just worked on because they had to.”2

Vincent worked in an exalted frenzy of emotion with speed and vitality. So excited was he when painting that he described the emotions as “sometimes so strong that one works without being aware of working … and the strokes come with a sequence of coherence like words in a speech or a letter.”3

Though Vincent struggled to find his place in the world, he did find delight in his craft and longed for this work to be shared by an audience in search of hope.

I love seeing such a clear picture of the delight in doing one’s vocation.

Vocation comes from the Latin vocatio, which means simply “calling.” The German reformer Martin Luther sketched three arenas of human calling: the household, the church, and the state. In Luther’s day, the household was the primary arena of work and economy. As part of the household vocation, you’d find agricultural work, artisan craft, and the rule of nobility (politics).

The reformers understood one’s work as an act of love and service to their neighbors and community.4 C.S. Lewis would agree.

In his address “The Weight of Glory” (1941), Lewis describes how Christians should view their daily activities in work and community. Lewis begins the address by questioning the ultimate point of Christian love. He asks: What is the reward of sacrificing oneself in obedience and following Jesus? His answer is the weight of glory. But what is that?

The weight of glory, says Lewis, is to be loved by God and to please him.

Lewis concludes his address by challenging the reader to realize it is their duty to worry more about their neighbor’s weight of glory than their own. In some way, each person should consider how to help their neighbor be welcomed and to find fame with God.

According to Lewis, we do this through relational sincerity—by taking one another seriously, realizing the divine worth of each human being, and remembering that our senses have not beheld a beauty like the beauty and holiness of our neighbor.

A kind of holy magic is enfolded into our daily acts of calling. By aiming to serve our neighbors with our gifts, abilities, and resources, we overlay society with what I like to call heaven culture.

But we must battle against human nature. The mercenary spirit of our age bends the aim of calling inward (incurvates en se), inflaming our desire to work for selfish gain at the expense and exclusion of others.

Overcoming culture's bent nature is a daily challenge. But it begins with letting God transform the way we think about our work.

When my daughters were young, I’d tell them, “As unto the King!” before they left for homeschool co-op. It was my charge to them to work for God; when you do, I’d tell them you’ll find joy.

Historians tell us that Vincent rejected Christianity after growing up evangelical and working as a minister in his twenties. But I think his vocatio tells us a different story. Though he was hounded by bipolar disorder, he was lucent most of the time, was renowned for his work ethic, sought to bring delight to viewers, and found characteristics of God in what he saw in nature.5 All we can do is speculate, but it was almost as if Vincent threw off the shackles of institutional religion and worked as unto the King.

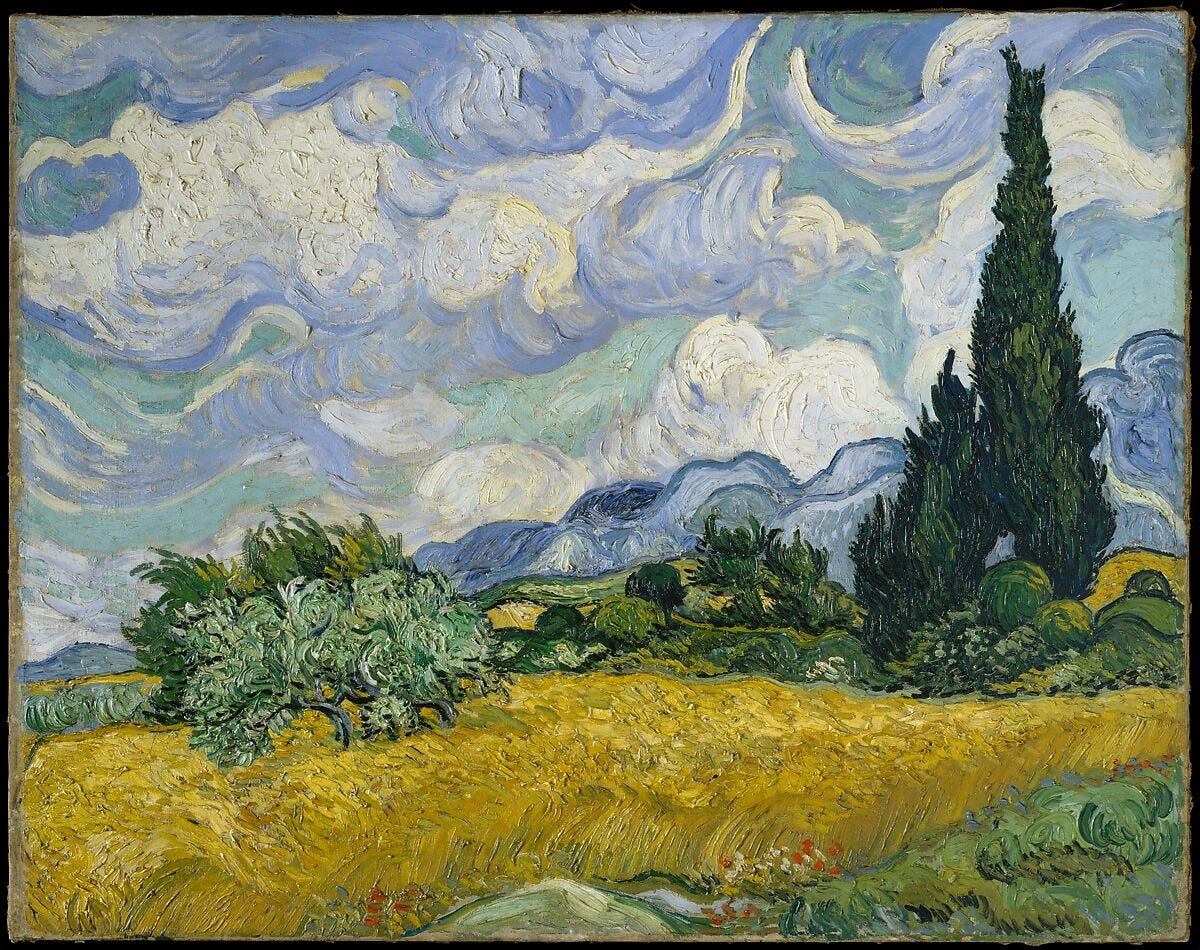

The beauty of Vincent’s work is in the delight the world continues to find in it, particularly in works like “Starry Night” (see notes below).

So, if I could encourage you today, it would be this.

In your vocation, don’t try to make a statement about yourself. Make a statement about your joy in pursuing what you love. In so doing, you will serve your neighbor and draw them further and further into God’s weight of Glory.

Notes

E. H. Gombrich, The Story of Art, 16th edition edition (Phaidon Press: Phaidon Press, 2007), 548-549.

Ibid., 548.

Ibid., 547.

The Apostle Paul told the first-century Corinthian church to “continue to live in whatever situation the Lord has placed you, and remain as you were when God first called you.” I Corinthians 7:17, NLT. Here, we get the theological concept of calling kaleo. There is some debate as to Paul’s use of calling here. Reformed thinkers generally link this idea to vocation in the Lutheran sense. Tyndale, New Bible, and Calvin's commentaries take slightly different approaches. But most seem aligned on how our daily work should be an act of loving service to others.

See Martin Bailey and Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum, Paperback edition (London: Frances Lincoln Publishing, 2022). See also Van Gogh’s Last Painting: Great Art Explained, 2024,

.Vincent Van Gogh’s The Starry Night: Great Art Explained, 2021,

The cypresses painting is one of my favorites--I fell in love when I stood before it and could not leave it, though my companions had walked on. It's bright hopeful colors and forms have been in my mind these last weeks as the Lord has planted the seeds of a new, beautiful dream that is too big for me, but fills me with delight. But your words about calling and that you chose that painting are of such encouragement, so I thank you!

Have you ever heard Matthew Perryman Jones song, “O, Theo”? It’s a beautiful meditation on Van Gogh and what you’re writing about here!